Maplopo Presents:

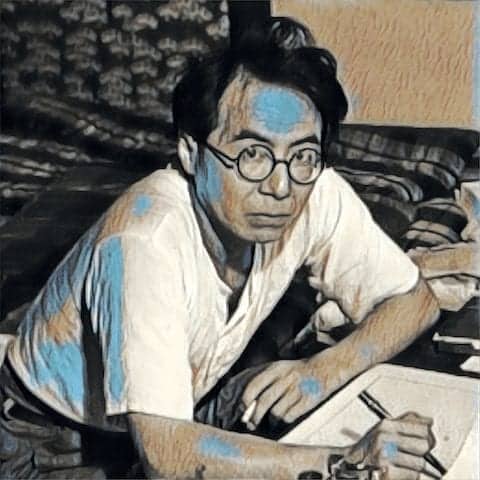

Sakaguchi Ango

Biographical Timeline

Sakaguchi Ango (1906‒1955) was a seminal novelist, essayist, and critic, who wrote for various magazines and newspapers, not only in the form of regular fiction and critical essays but also across genre: writing folk tales, detective stories, historical novels, autobiographical stories, travelogs and social commentary.

Last updated: February 12, 2022

This page is also available in Japanese.

Ango started self-publishing translated works of French literature with his literary friends at the age of twenty-four. His first recognition came in 1931 at twenty-five when he published his novels, “Kaze hakase” (Professor Blowhard) and “Kurotani mura,” which were well received in literary circles. His popularity was established with publication of the essay “Darakuron” (Discourse on Decadence, 1946) and the novel “Hakuchi” (The Idiot, 1946). These powerful, provocative works resulted in Ango’s being labeled a buraiha (libertine) along with such authors as Dazai Osamu, Oda Sakunosuke, and Ishikawa Jun.

The more Ango’s abundant intelligence and humanistic quality is recognized, the more admiration of him grows, even six decades after his passing. And the phenomenon goes beyond the borders of Japan.

One of the most prominent researchers/scholars of Ango is Nanakita Kazuto (1961‒). He began his involvement in the compilation of the definitive edition of Ango’s work, Sakaguchi Ango zensyū (the complete works of the author) in 1997. Among his writings on Ango, his Hyōden Sakaguchi Ango—tamashii no jikenbo (2002) has been highly praised among critics and Ango’s hardcore fans alike. Alongside Ango’s son, Sakaguchi Tsunao, Nanakita is the primary contributor of the Sakaguchi Ango Digital Museum, and writes most of the articles.

Another notable admirer of Ango is a contemporary Japanese writer, Ogino Anna (1956‒), an established scholar and professor in the department of literature at Keiō University. Her passionate book, I Love Ango (1992) has contributed to further interest among contemporary audiences.

Sakaguchi Ango, who was known to be forthright and to give his all to everything he did from writing to gallivanting, continues to attain a wide readership that surpasses time, and spans the globe as more readers acknowledge what a truly transcendent thinker he was.

The Life of Sakaguchi Ango

Works cited:

Ogino Anna. “Paradox at Play: Ango as Japanese Humanist.” Literary Mischief: Sakaguchi Ango, Culture, and the War, ed. James Dorsey and Doug Slaymaker, trans. James Dorsey, Lexington Books, 2010, pp. 35.

Sakaguchi Ango. Afterword and timeline. Kaze to hikari to hatachi no watashi to, Izuko e, afterword and timeline by Nanakita Kazuto. Iwanami bunko, 2015, pp. 403-420.

1906

October 20: Sakaguchi Ango is born in Nishi-Ōhatachō, Niigata as the fifth son of Niichirō and Asa Sakaguchi’s nine children—the twelfth overall out of thirteen. Ango’s birth name is Heigo. His mother’s family, Yoshida, is a powerful landowner. His father, a member of the Diet in the Lower House of Representatives, is president of Niigata Shinbun-sha, and board chairman of Niigata Rice and Grains Stock Exchange Company; he is also a poet of classical Chinese poetry in the Mori Shuntō style.

1913

Enters elementary school. Righteous minded, Ango is a ringleader of kids with an abundant sense of justice. Throughout his six years of elementary school, his grades have always been high, placing him second or third to the top of class. He is appointed to the equivalent of the dean’s list each year. He is good at sports as well, and performs honorably at the city’s sumō wrestling and sports festivals.

1919

Enters Niigata Junior High School. Begins reading novels written by Akutagawa Ryūnosuke and Tanizaki Junichirō, but at the time is more fond of reading sports magazines.

1920

Starts skipping school frequently. His nearsightedness worsens and a rebellious sentiment toward tyrannous teachers and seniors grows during this time. As a result, his grades dip. He often plays the card game, hyakunin isshu, with his truant friends. He comes to school after classes are over and practices judō and track and field.

1922

Expelled from junior high school in the summer of his third year on account of punching a teacher. Transferred to Busan Secondary School in Tokyo. Becomes close friends with Yamaguchi Shūzō and Sawabe Tatsuo. Often sits in Zen meditation with the philosophy-minded Sawabe.

When Ango had to withdraw from junior high school, . . . legend has it that he left carved inside the top of his desk the now famous phrase he himself was so fond of quoting: “I shall be the grand delinquent, rising again one day in the annals of history.”

1923

His passion for creative writing deepens with increasing amounts of reading. Reads the works of Anton Chekhov, Masamune Hakucyō, and Satō Haruo often. Among his favorites are Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Baudelaire, and Ishikawa Takuboku. Interested in books on religion and natural philosophy as well. On November 2nd, his father dies of retroperitoneal tumor.

1924

Wins first prize as high jumper in nationwide secondary school athletic meet. Does well at school sports festivals, and in sumō and judō tournaments.

1925

Graduates from Busan Secondary School and becomes a substitute teacher at the Shimokitazawa branch of Ebara Jinjyō Elementary School.

1926

Resigns his position as substitute teacher. Enters Tōyō University as a student in the philosophy and ethics department. Lives around the Ikebukuro area moving from one place to another with his older brother, Hozue, and his aged wet nurse. Immerses himself in the reading of books about Buddhism and philosophy in an attempt to achieve a state of enlightenment. Makes it a rule to wake up at two in the morning each day as part of ascetic training.

1927

Hit by a car, and suffers a skull fracture. Symptoms of depression gradually start to show. Constantly suffers from auditory hallucination and tinnitus, and has difficulty walking. Throughout the fall and winter, pays a daily visit to his friend, Sawabe Tatsuo, who is hospitalized for mental illness at Sugamo Sanatorium.

1928

Becomes an enthusiastic language learner. Learns Sanskrit, Pali, and Tibetan all at once. In April, enters a language school, Athenee Francais, and learns French and Latin too. Is fond of novels by Poe, Baudelaire and Beaumarchais and focuses on reading French literature. Among Japanese writers, Kasai Zenzō, Uno Kōji, Arishima Takerō are his favorites. Reading Chekhov’s “A Dreary Story” inspires him, and he writes a novel for the first time at the age of twenty two. Submits the work to Kaizō’s prize competition but loses.

1930

Graduates from Tōyō University. That summer, begins planning for the publication of a self-published magazine with friends from Athenee Francais, as a way to share their own works with people of similar beliefs and ideas. Among those friends are Kuzumaki Yoshitoshi, Eguchi Kiyoshi, Nagashima Atsumu, Wakazono Seitarō. They work together doing translations at Kuzumaki’s every day of the week, all night long. In November, their magazine, Kotoba, is launched. Ango serves as co-editor and co-publisher with Kuzumaki.

A natural progression of events led to the self-publication of a magazine of translated works named, Kotoba, and later, a dōjin magazine, Aoi uma; Akutagawa Ryūnosuke’s study was used for the editing. Reason being, one of the members, Kuzumaki Yoshitoshi, was Akutagawa’s nephew; Kuzumaki was young, twenty-one or twenty-two at the time, and doing a great job bearing the responsibility of putting things in order after Akutagawa’s death and publishing the deceased author’s complete works. He was more familiar with self-publishing than us, so he served as lead. This was the third year after Akutagawa’s passing.

*a dōjin magazine refers to a type of magazine which features works by people who share the same ideas and possess a similar mindset.

1931

Publishes his first ever novel, “Kogarashi no sakaba kara” (From a sake warehouse in the winter’s wind) in the second issue of Kotoba. In May, changes the name of the magazine to Aoi uma and publishes its first issue under Iwanami Shoten. Hishiyama Shūzō joins as a new member. In June and July, Ango’s “Kaze hakase” (Professor Blowhard) and “Kurotani mura” receive rave reviews from Makino Shinichi, making Ango’s name instantly familiar to those in literary circles. In October, his serialized novel “Takeyabu no ie,” begins its run in Bunka for which Makino is an editor. From that point forward, he gets better acquainted with Bunka members such as Kawakami Tetsutarō, Nakajima Kenzō, Kobayashi Hideo, and Miyoshi Tatsuji.

1932

With an introduction from Kawakami Tetsutarō, Ango visits Ōoka Shōhei in Kyōto. Rents a room in an apartment from Ōoka’s friend, Katō Hidemichi, for a month. In the fall, makes Nakahara Chūya’s acquaintance in a bar, Windsor, located around the Kyōbashi station in Tokyo as well as, waitress, Sakamoto Mutsuko, and comes to know her quite well.

1933

Meets rising novelist, Yada Tsuseko, falls in love, and enters into a relationship with her. In March, Yada invites Ango to join the self-published magazine, Sakura, where he helps with its launch. Among its members are: Tamura Taijirō, Inoue Tomoichirō, Masugi Shizue, and Kawata Seiichi. Around this time, Ango lends a hand organizing the plans for Kigen, another self-published magazine, incubated by Oki Kazuichi and Wakazono Seitarō; he then gets Nakahara Chūya to join in. In April, crushed once he discovers Yada Tsuseko is having a love affair with Wada Hidekichi, an executive staff member of Jijishinpō (a newspaper company). In July, Yada is taken into custody by the Special Higher Police for ten days (on suspicion of providing the Japanese Communist Party with monetary support).

1934

Ango’s best friend at the time, Nagashima Atsumu, dies of encephalitis, and Kawata Seiichi, for whom Ango cares a lot, passes away at the age of twenty two. In the spring, begins living with Oyasu, the female bartender of the bar, Bohemian.

1936

Receives a letter from Yada Tsuseko in March; the letter proposes she and Ango break off their relationship completely. That same month, Makino Shinichi (who played a part in Ango being recognized, see 1931) commits suicide; Ango later attends Makino’s funeral. In June, sends his last letter to Yada Tsuseko.

1937

Begins to stay in Kyōto around the end of January and ends up living there until June the following year. Reads many classic works of Japanese literature such as essays from the Edo period.

1940

Meets Ōi Hirosuke on New Year’s Eve, and agrees to join Ōi’s self-published magazine, Gendai bungaku.

1941

Spends days and days at Ōi Hirosuke’s having fun playing guessing games where the criminals of detective novels need to be correctly guessed by the members of Gendai bungaku, including: Hirano Ken, Sasaki Kiichi, Ara Masahito, Minamikawa Jun, and Inoue Tomoichirō.

1942

In February, Ango’s mother, Asa, passes away. In March, he publishes “Nihon bunka shikan” (A Personal View of Japanese Culture) in Gendai bungaku. In June, publishes “Shinju” (Pearls) in Bungei.

What makes these three things—the prison, the factory, and the destroyer—so beautiful? It is the fact that no frills have been added for the sake of beautifying them. Not a single pillar or sheet of steel has been added in the interest of beauty; not a single pillar or sheet of steel has been removed because it is not aesthetically pleasing. That which is needed, and only that, has been placed precisely where it is needed. . . . The very same thing might be said about my work, literature. To add even a single line to a work of literature simply for the purpose of making it beautiful is unacceptable. Beauty is not born where one is consciously trying to create it. There are things that we absolutely must write and things that absolutely must be written. Our job is to compose only in accordance with those uncontrollable needs. It is all, from beginning to end, a matter of “necessity,” and that alone.

1944

Becomes a temporary employee at Nippon Eiga Sha (a movie company) to avoid being drafted. In March, Yada Tsuseko passes away.

1945

The war ends on August 15. His family’s house in Kamata, Tokyo survives the fires.

1946

In April, publishes “Darakuron” (Discourse on Decadence), and in June, “Hakuchi” (The Idiot), both in Shinchō. They attract major attention, instantly making him a popular writer. To deal with a flood of requests for writing, Ango regularly uses methamphetamine and drinks alcohol in excess. On November 22, he attends a meeting along with Dazai Osamu, Oda Sakunosuke, and Hirano Ken, designed to facilitate a discussion about contemporary novels, and three days later on November 25, does another round-table discussion with Dazai and Oda. In December, attends Doyōkai (Saturday meeting) hosted by Edogawa Ranpo.

The fall is not the result of having lost the war. We fall because we’re human; we fall because we are alive. Nevertheless, humans cannot fall forever because they’re not immune to emotional hardship. Humans are pathetic, they’re frail, they’re laughable. All the same, they’re simply too weak to fall to the very bottom. . . . Only by falling to the very depths can [Japan] discover itself and thereby attain salvation. Redemption through politics is but a surface phenomenon and not worth much of anything.

1947

Publishes “Kaze to hikari to hatachi no watashi to” (Wind, Light, and the Twenty-Year-Old Me) in Bungei, and “Watashi wa umi o dakishimeteitai” (I Want to Be Holding the Sea) in Fujin gahō. On January 10, Oda Sakunosuke dies of tuberculosis. In March, meets his future wife, Michiyo. In April, publishes “Ren’airon” (Discourse on Love) in Fujin kōron. Around this time, Michiyo suffers from peritonitis and an emergency operation is performed; Ango attends to Michiyo for one month in the hospital, never leaving her side. After being discharged from the hospital, Michiyo begins to live at Sakaguchi’s, gradually recuperating. Publishes “Sakura no mori no mankai no shita” (In The Forest, Under Cherries in Full Bloom) in Nikutai. Ango’s first detective novel, which is serialized, “Furenzoku satsujin jiken,” begins its run in Nippon shōsetsu. Continues to take stimulants, including the usage of amphetamine in addition to methamphetamine.

1948

Dazai Osamu and Yamazaki Tomie, having entered into a lovers’ suicide pact, throw themselves into the Tamagawa Aqueduct on June 13. Two days later, on June 15, Ango receives the news of their deaths. In July, publishes “Furyō shōnen to kirisuto” (The delinquent boy and Christ) presenting his original theory about Dazai and civilization. Continues to suffer daily from insomnia and takes sleeping pills in excess while carrying on his regular stimulant usage. Both visual and auditory hallucinations appear.

1949

Undergoes a number of crazed fits from an excessive intake of sleeping pills, resulting in such disturbances as Ango jumping from a second floor window and exerting violence on people in his home. In February, hospitalized in the University of Tokyo Hospital neurology ward. In April, receives a notice of property seizure from the tax office due to his tax arrears, and in protest, submits a letter of objection. In August, experiences a recurrence of fits from sleeping pill addiction; held in custody at the police station. In the winter, gets a dog, allowing him to gradually return to a healthy lifestyle through the habit of walking a dog.

1951

In May, sits in on a public hearing of the first trial of the Chatterley case. (The Chatterley case refers to a legal case where the translator, Itō Sei, and the publisher of D. H. Lawrence’s novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, are prosecuted under Article 175 of the penal code for distributing obscene documents.) In November, falls into near insanity from taking an excess amount of sleeping pills in one go and orders one hundred bowls of curry rice from a nearby restaurant, and has them delivered to Dan Kazuo’s where Ango is currently staying.

1952

Publishes “Yonagahime to mimiotoko” in Shinchō.

1953

In June, travels with Dan Kazuo from Niigata to Matsumoto, Nagano to obtain research material for a magazine project. During the trip, Ango makes a commotion and acts out violently, which results in him being detained in police custody. As soon as he is released, hears news about the birth of his son, Tsunao. Returning from the trip, Ango makes another wild commotion and finds himself back in custody. Later, he submits to city hall a letter of apology to the mayor, and registers his marriage and the birth of his newborn son.

1954

In August, resigns his post as Akutagawa award selection committee member for which he has been a part of for five and a half years, having shown doubt regarding its selection process. In October, goes home to Niigata with his wife and son for a customary memorial service for his parents.

1955

In February, his serialized travelogs, “Ango shin’nihonfudoki,” begins its run in Chūō kōron. On February 17, dies of cerebral hemorrhage at home at the age of forty-eight. After Ango’s death, “Aoi jūtan” (The Blue Carpet) is published in Chūō kōron.