Susumu Nakanishi’s “The Japanese Linguistic Landscape”: An Insightful Treasure Box Brimming With Goodness

In the carefully curated collection of essential Japanese words that is The Japanese Linguistic Landscape, NAKANISHI Susumu skillfully takes us through the beauty of the Japanese language, and helps us explore the contours of its linguistic terrain. It’s a completely different type of book—an enjoyable gathering of 95 essays from the refined scholar Nakanishi, whose own virtue and grace eloquently permeate the page. Far from being a monotonically delivered treatise on language, The Japanese Linguistic Landscape is bounding with life, like the words Nakanishi highlights within. Reading each narrative is like savoring a book full of bonbon chocolatesーa real treat, and the creativity and effort that went into organizing such a work, worth appreciating.

Aside from the book’s ability to help us learn quintessential Japanese words, The Japanese Linguistic Landscape also provides an opportunity to glean a bit of insight into the character of Nakanishi himself. If we strive for the perceptual capacity to soak up this essence, there is a lot of soulful nourishment to gain. I found this tasteful, mind-nurturing book very valuable, and I’m so glad to have happened upon it. I believe you will find it equally meaningful.

A note on this review: When you find a book that blows your mind and moves you tremendously, you want to continue to reflect upon it, live by it, and carry its message in your heart. This book is that sort of book for me. It has great messages I wish to adopt and bend to my life. Since the book is compartmentalized in a series of single essays, it’s tailor-made for separate reviews on those individual essays. Which is, exactly what I’ve decided to do. So, I want to continue to write about Nakanishi’s work as I reflect on it, and deliver my write-ups as a series. I honestly don’t know how many posts it will be, but I’m very excited about sharing… for, how pleasingly these ideas and his writing have affected me.

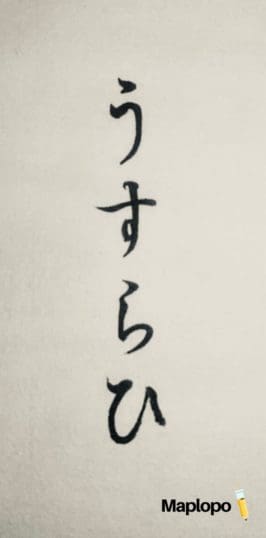

Usurahi (うすらひ) (p.80)

Today, I’d like to share three particular essays that, I think, give me a glimpse into Nakanishi’s noble character. The first, usurahi (うすらひ), highlights a certain aspect of his innocence.

One day, while staying at a temple in Nara, Nakanishi hears about the discovery of a well that has been hidden from sight for a millenia. The well is located upon the grounds of an Asuka period imperial palace. He recognizes immediately this is a big deal. So, the next morning he heads out into the wintery cold to see for himself this incredible find. As the well comes into view, he notices a thin coating of ice on the surface of the water. He murmurs to himself immediately, “Ah, usurahi!”

Now, before having read this segment, admittedly, I’d never heard of this word, usurahi. Let alone possessed the knowledge as to how to use it. Kori (氷), on the other hand, is a simple, basic term for ice, so, in the same situation, I’d likely use that word instead. What’s beautiful about this scene is that in an instant Nakanishi knows precisely what word to use in describing this fragile layer of ice— delicate enough to fracture at the mere touch of a finger—the kind of ice you only see at the beginning of winter when it just starts to feel chilly outside and you know, “Oh, winter is coming soon!” By sharing his memory and describing it so adeptly, Nakanishi calls attention to the sort of thing we’re inclined to look over. Because he allows me and the average reader to relive the moment as he experienced it, in the future when I encounter it, I’m more likely to end up paying such an occurrence more attention. By encapsulating the meaning of usurahi so well, and wrapping such a memorable story around it, Nakanishi increases the likelihood that I may end up using this beautiful word that before now had drifted into oblivion and was waiting to be discovered by me.

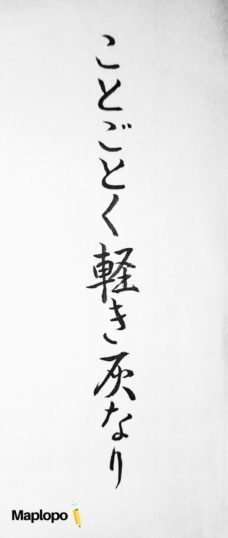

Unbearably Light Ashes (ことごとく軽き灰) (p.294)

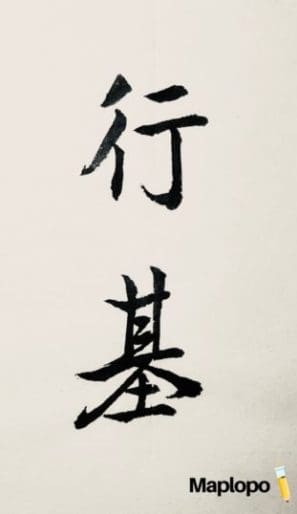

In another segment, Nakanishi shares a story about paying a visit to Chikurinji-temple (竹林寺) in Nara. There, he stood before the grave of Gyoki (行基), a famous monk from the Nara period who devoted himself to the common people, and supported the creation of many public works projects: irrigation, temples, bridges, and lodging for travelers. In the essay, Nakanishi shares his sadness in thinking of Gyoki’s life. It was a challenging one filled with much hardship. Gyoki had no interest in worldly fame, and simply wanted to serve the people who needed him most.

But, like any other charismatic religious practitioner, he was repressed by the government because of his influence in the community. Giving strength to the people in ways the government could not, made him a threat. He never stopped fighting for his faith, though, and worked his butt off doing good for society. As a result, he saved thousands of people spiritually—selflessly giving of his time and energy to the suffering and trials of the people. When he died and was later cremated, his admirers and disciples were said to have cried their hearts out over the realization that all that remained of their beloved master were those unbearably light ashes (ことごとく軽き灰). That his ashes lacked weight showed how his bones were brittle—a reflection of the degree of hardship he must have gone through in his lifetime.

The manner in which Nakanishi narrates his thoughts from that day at Chikurinji-temple—the way he introduces the monk’s challenging life and humble commitment to hardship—is done so eloquently I’m able to deeply empathize with Nakanishi’s strong emotion from that day. These ashes once represented a live human being; a human being of such vast charisma and virtue. Yet, without exception, even for this person of goodness, life for each of us is one where we return to ashes. Our body returns to nothingness. The moment we’re born is the moment we’re headed to our end.

To be sure, this idea of opposites appears in most concepts; that of two contradicting things; two sides of the same coin. Yin and Yang. Nakanishi’s philosophical contemplation of Gyoki’s life and the poignancy of Gyoki having brittle bones and being reduced to unbearably light ashes, shows me once again, the author’s beautiful character.

When I read this story, I saw beauty in it and was reminded of how I tend to appreciate that which is no longer among us as beautiful. Sakura in spring is the perfect embodiment of this idea for us in Japan. My husband, Doc, though, still maintains a sense of wonder over this ability to reflect so positively about something he sees as “missing.”

When we were discussing this chapter we recorded a portion of it so I could come back to it. At one point, he asked: “Why is it beautiful? Why doesn’t it register as grief, or pain when you’re left without the thing you love? We (Americans), I think, tend to see it as “pain” because it’s gone. But you (Japanese) are good at appreciating temporary beauty. We tend to be stuck with the last feeling and forget the feelings before that. We remember the last thing, what we’re left with. So if someone we love dies, we tend to think, “Ah! Why are they gone?!” We don’t like that they’re not here anymore. We have to fight to get to that feeling of appreciating loss as beauty—that ability is awe-inspiring… this is what religion is trying to teach us all the time but it’s difficult.”

He is right. It is difficult, and these are all good questions. And, I’m certainly unqualified to tackle the topic head on.

Perhaps, though, Japanese people may have a unique sense for appreciating whispy, ephemeral beauty—and sometimes, in doing so we associate loss with that sense of beauty.

Keeping in mind that nothing will last forever, indeed reminds me of life’s ephemeral beauty—and the truth about life: we all come from the tiniest of elements, and after blossoming and experiencing all sorts of excitement in our short lives, we all have to revert to being that tiny thing once more. Maintaining this realization and reading about it in this passage truly moved me.

*As a side note, writing this piece reminded me of the time I shared with Doc the Japanese classic, The Crane of Gratitude (鶴の恩返し). That story as well, represents this sad, ephemeral beauty we tend to appreciate in Japan, but he was a little puzzled by my appreciation of it.

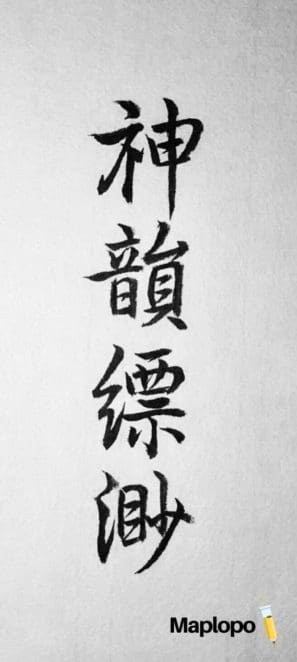

Shinin Hyobyo (神韻縹渺) from the essay, Accumulate Virtue! (p.282)

This particular passage in the book I really liked because it finally enabled me to express things I’ve been wondering, or thinking about, and talking with Doc about a lot. Which is, “why is one moved by certain works of art and not others?” What is it that we sense in “true” artistry that moves us? Is it something the artist themselves possess, or is it something within the piece?

Nakanishi asserts this difficult-to-define quality that true artists seem to have in common can be described as shinin hyobyo (神韻縹渺): “[…] The sense of authenticity that emanates from masterpieces stems from their ability to go beyond mere representation, beyond mere portrayals of actual form. Instead, what emerges from these canvases is a fragrance of the very divine, mystic air itself” (p.282). It’s that special feeling you get when art really strikes you… it’s the spirit of the artist.

Take for example, the written word. As Nakanishi sees it, and I agree, one can totally lack shinin hyobyo even if one is skilled, even if one is in command of one’s grammar, and even if one is a prolific user of words most of us would have to reach for a dictionary to understand.

On the other hand, a writer can truly move a reader, and be in complete possession of shinin hyobyo, without these things. For instance, a writer can have grammar so all-over-the-place that readers want to tweak it a bit (as Haruki Murakami once commented about Nobuo Kojima’s writing), and yet still move the reader. Sure, to Murakami, Kojima’s grammar might need a bit of editing, and his writing may be a bit strange (in a most positive way), but still, his short story, 馬 (horse) is what Murakami considers a masterpiece, and I totally agree!

Most of us can tell when an artist’s heart is no longer “in it.” Or, if it was never there to begin with. Things feel plastic, stiff, or formulaic. I think this is a bit of what Nakanishi is unearthing when he references shinin hyobyo. When, despite all the “errors” and oddities, if the piece still moves people, then it’s real. That to me is the essence of shinin hyoybo.

This concept is very difficult to define and explain in a structured way in Japanese, and doubly so when translating it in English. Yet, Nakanishi and his translator, Ryan Shaldjian Morrison, successfully characterize the concept beyond all difficulty. Together, they’ve delivered a narrative in both Japanese and English that makes sense, and sticks—a theme that runs throughout the book. I don’t know how Morrison found all these words to match, how much time he spent to do research (unfathomable!), or how he stayed so loyal to the original text, but he did. It’s very much worth admiring, and I wish to acquire this skill myself at some point as I strive forward.

On that note, in the Japanese version I can clearly sense Nakanishi’s shinin hyobyo shining through on each page. And, in the English version, the translator’s effort, hard work, and the amount of respect and dedication paid to the original Japanese allows the reader to pick up on both Nakanishi’s shinin hyobyo, and Morrison’s as well.

To wrap! In the next installment, my write-up will cover the essay, The Words of Shinran (p.288) (親鸞のことば). Thanks so much for reading.

More about Nakanishi's The Japanese Linguistic Landscape:

Purchase it here:

The Japanese Linguistic Landscape: Reflections on Quintessential Words by NAKANISHI Susumu. Translated by Ryan Shaldjian Morrison.

The Japanese Linguistic Landscape: Reflections on Quintessential Words by NAKANISHI Susumu. Translated by Ryan Shaldjian Morrison.

Published by: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture (JPIC)

ISBN 978-4-86658-068-5

First English edition: August 2019

This book is a translation of Utsukushiki Nihongo no Fukei (美しき日本語の風景) and selections of Part I and II in Kotoba no Kokoro (ことばのこころ)

NAKANISHI Susumu (Author)

Nakanishi was born in Tokyo in 1929. He earned his doctorate in literature in 1959 from the University of Tokyo. In 2013, he was awarded the Order of Culture, Japan’s top prize for cultural contribution. He was awarded the Yomiuri Prize for Literature in 1964, the Japan Academy Prize in 1970, and Watsuji Tetsuro Culture Prize in 1991 for his pioneering work on the Manyoshu (万葉集)ーJapan’s oldest poetry anthology. He has been appointed poetry composer for the annual Utakai Hajime (First Poetry Reading) held at the Tokyo Imperial Palace. In 2004, he was recognized as a Person of Cultural Merit. In 2005, he was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure.

Ryan Shaldjian Morrison (Translator)

Morrison is a literary translator and scholar of Japanese literature. He is currently a tenured lecturer at Nagoya University of Foreign Studies. He received his first M.A. in Japanese literature from Arizona State University in 2004, his second M.A. in Japanese literature from Sophia University (Tokyo) in 2009, and his Ph.D. from the University of Tokyo in 2016 for his dissertation on the modernist writer ISHIKAWA Jun.