If you’re new to this series, each write-up centers on the work of Susumu Nakanishi’s The Japanese Linguistic Landscape. This is the second in the series. You can find the first, by visiting “The Japanese Linguistic Landscape”: An Insightful Treasure Box Brimming With Goodness.”

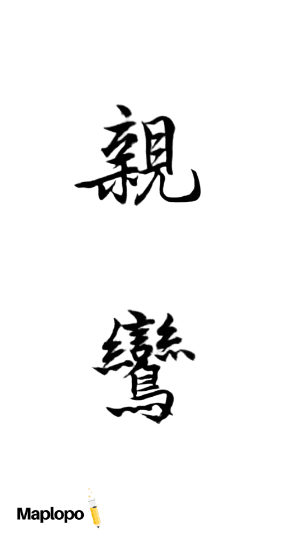

“The Words of Shinran” (親鸞のことば) (p.288-293)

As I was saying in my last post, today I’d like to focus on Nakanishi’s essay entitled, The Words of Shinran (p.288-293). Shinran was a charismatic Buddhist monk who lived in Hino, Japan (modern-day Fushimi, Kyoto) nearly 900 years ago (1173-1263). He is so revered for his humanistic teachings, and given strength to so many Japanese, that many refer to him as a “king of humanity.” Nakanishi, as well, seems equally fond of him, having written about him previously, and the apparent owner of many books about the storied monk.

I too am fond of Shiran and the Jodo Shin / True Pure Land sect he founded, because my father has led a temple as a Jodo Shin monk for fifty-four years since the age of twenty-six. Growing up in a temple family, I certainly knew of Shinran and his teachings, but I never came to know, nor paid due attention to his character, to what sort of person he was. So, as I was reading Nakanishi’s essay on Shinran, his enthusiasm and admiration for this remarkable monk made an impression on me.

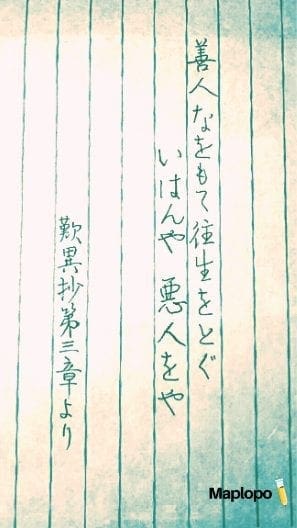

In Nakanishi’s essay, he references Shinran’s most radical and well known thesis, akunin shoki. The thesis appears in Tannisho (Notes Lamenting the Differences), a collection of conversations between Shinran and a disciple, Yuien, and states: “If a good man can be reborn in paradise, a bad one can be all the more so!”

I’m sure to embarrass myself by saying this, but I was very confused. “That doesn’t make sense,” I thought. “Why, of all people, are bad people favorably-picked and given access to paradise? What about good, honest, hard-working people? Why are bad people even considered for a pass to paradise in the first place?” Doesn’t such a philosophy send the wrong signal to those inclined to indecorous behavior, effectively warranting their desire to commit evil acts because rebirth in paradise remains a possibility? This whole concept made me stop a bit, so I phoned my father for a better explanation and interrogated him on this subject.

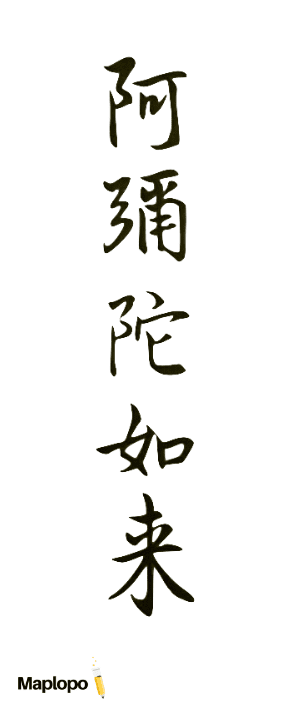

After several phone calls, and thanks to his interminable patience, I gained quite a profound understanding of this weighty pronouncement by Shinran. Noting there were numerous interpretations among scholars regarding akunin shoki, my father took to explaining the concept by re-introducing Amida Nyorai to me. Amida Nyorai is a benevolent figure whose lifeforce pulses throughout the universe, and whose light illuminates the darkness of the entire world. Amida Nyorai embraces the foolish, and prioritizes ordinary sentient beings: those of us who are inherently weak, lazy, egoistic, and helpless, rather than the grand or nobel. Or, those who proudly consider themselves significant and strong, and capable of carrying out difficult religious practices no matter how strenuous and arduous they may be.

So, my understanding of akunin (a bad person), wasn’t adequate. It’s not about “bad” in a contemporary, black and white kind of way; the word has a more profound and complex meaning. It’s about us. It’s about that side of “us” which sometimes gets lazy, crazy and naughty, and does stupid things from time to time. That version of us who pollutes, lies, thinks selfishly, does things to others that we’d prefer weren’t done to us, and who possesses a “dirty heart,” as my father says.

Shinran knew this very well, says Nakanishi. He knew it to his very marrow. He was acutely aware of his own weakness, ego, and passions in life, calling himself Gutoku—a bald fool. He was a real human being, willing to accept that fact, and far from hypocritical. Note, he didn’t “positively affirm lust and worldly fame,” though. Rather, he was simply gazing at his own natural human needs with clear eyes.

I imagine when he was serving at the Enryakuji temple as a menial monk, he may have had occasions where he felt angry at unreasonable criticism or scorn; he could’ve thought enduring all those required inefficient religious practices was absurd; he might’ve salivated over the infectious appeal of wide acclaim. Also, I’m sure as he entered puberty, he snuck a glance at a beautiful girl that walked by the temple and eventually fell in love. (That would be romantic.)

But he was also surrounded by, and given a righteous doctrine, from adults. He was also given a vision of a perfect world where he should seek truth and be pure. He apparently respected this idea and recognized the goodness of Buddhism. And, wanting to keep his faith and be as great a monk as he could be, I must imagine the awareness of this contrast must’ve created huge conflict within his young mind. This conflict may be why we see frequent mention of sadness in stories about and from Shinran. But, in being torn and wanting to search for a solution he and others could benefit from, he ended up creating a path that’s never beyond the reach of the ordinary person, still to this day.

That path was essentially one of balance. One that would allow each of us to participate in a life of piety as well as a life comprised of human wants and needs. Shunning either, seemed an inadequate answer to him. So, he ended up envisioning a seesaw—placing faith on one side and his human-ness on the other. If we were to do that, we would achieve a life that was level.

This unique idea endeared Shinran to me, Nakanishi, it seems, and many other ordinary Japanese—an idea I feel might benefit from some further fleshing out.

In the thirteenth century when Shinran lived, Buddhism was more akin to “an ideological weapon of the state,” than anything else. The religious establishment had become so powerful it held much sway with the nobility and gained great wealth from the authorities and upper classes. As such its doctrine was way out of reach for the masses. And yet, he was there for them: merchants, blacksmiths, fishermen, farmers, wives, prostitutes. All weren’t afforded the opportunity to care about faith even if they wished to, because in their lives, they had real things to do. Laundry to wash in the nearest body of water, a floor to clean, kids to watch out for… meals, health concerns, and on and on. They couldn’t possibly have the room for luxury in their schedule to practice strenuous religious practice, read and analyze difficult religious scholarly books (if they even could read); those were all activities reserved for religious aristocrats.

And so they wondered: “Do we still have the prospect of salvation? Do we have the choice to go anywhere but hell?” Because without that sort of study, they believed that was where they were destined to arrive. “I’m so out of practice,” “I’m hardly devout,” or, “I’ve never prayed to Amida Buddha… do I still have a chance?” And, then along comes Shinran. He invites them under his umbrella and says, yes, there is a way. You can still gain from the power of faith, and it will help you live through hardship. Have faith and do this one easy thing: recite the sutra. Have faith despite your ego, despite your concern, despite your pre-occupations.

Shinran’s influence has been immensely far-reaching, of course. So much so that many authors have written about his teachings. One example is TONOMURA Shigeru’s autobiographical novel Miotsukushi, which, thanks to Nakanishi’s identically entitled essay Miotsukushi (p.96), I got to know. It’s a bare and purely honest account of Tonomura’s life, with a heavy dose of his sexual history. Although I was a bit taken aback by the candor, it was an interesting read, and his thoughts on Shinran, really caught my attention.

In the book, Tonomura mentions that he’d read Shinran’s Tannisho. But, something about it rubbed his brain cells the wrong way because Tonomura’s preconceived notion of Buddhist monks needing to be saint-like was far from how Shinran was describing himself. Shinran was, in a way, too real and too objective for Tonomura. Shinran was pro-human; he accepted and embraced the foolishness of humans, our weakness, our insignificance. And, Tonomura was bothered because he wasn’t mature enough to accept this concept when he read Shinran’s Tannisho for the first time.

His moral ideals, strive for the Puritanical, and belief that one actually had the capacity to rid oneself of temptation and desire, ran counter to what Shinran was suggesting. And, yet, in observing his dissonance over Shinran’s teachings he at least could see that his own position was like “feeling openly glorious for being a virgin while still guilty of masturbating.” Later in life when he revisited Tannisho, Tonomura found himself understanding Shinran’s perspective, and gradually accepted his own foolishness. He was finally able to peer straight at the reality of what it’s like to be human without deceiving himself, and understand that the candid nature of Shinran’s words were supported by a merciful warmth served to aid helpless humans.

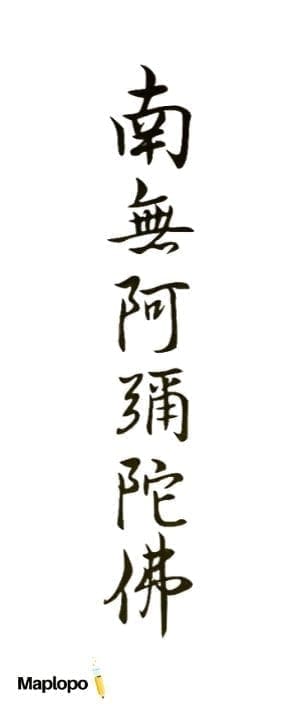

Coming back to my earlier mention of conversations with my father… on one of those calls he said reciting Namu Amida Butsu—“I take refuge in Amida Buddha” is a way to show gratitude to Amida when experiencing goodness as a result of faith. While some interpret Amida as having form, I like to think, personally, of Amida as an invisible power acting as a source of strength and providing me with a sense of well-being, and the spirit to not give up on myself, others and life. Having faith in Amida is like believing I can leave everything to Amida. Things’ll get better eventually if I have faith and keep my humility.

Life is inevitably messy. Sometimes, we feel sad, angry, and have all sorts of negative feelings. Occasionally, we can’t change things no matter how much we’re disheartened and have to surrender to what it is; once in a while you will have to sit through the most torturously boring meeting for hours and create a meaningless report for someone simply out of formality. You will have to take stinging insults from someone who doesn’t even realize their words have just crushed your feelings. You will have to come to terms with the fact your mother doesn’t know how to show love to her children. There is no way life is only filled with fairytale butterflies and flower fields. However, there are times we encounter love and hope, and feel blessed and grateful for what life brings.

I’d like to share this little story of what happened one day while I was briskly walking to work. I was holding my scarf in my hand, and apparently dragging the end of it on the ground as I race-walked. A woman came up to me running, and showed me how my scarf was dragging and getting dirty. Not only did she have the warm courage to speak to a complete stranger whose ears were plugged into earphones, but she actually ran to me in the sluggish commute of morning to let me know just that, thinking of me. It was a very heartfelt moment.

As I was thanking her, I was reminded that I should also thank that invisible power which I characterize as Amida. I feel this power of the universe is watching over me, so that I, this insignificant being, doesn’t drown for too long in a sea of disappointments and can swim through life and appreciate things.

Again, I’m very grateful for the opportunity to read and think a lot about this cool guy, Shinran. He’s indeed a fascinating character who I want to continue digging into. I certainly want to study more of Tannisho, and speak with my father again about it.

If you’re interested in Shinran and his thoughts, I’d recommend Tariki by ITSUKI Hiroyuki which Nakanishi mentions is in his personal “Shinran” collection. Tariki is an incredibly well-conceived body of work from a humble and thoughtful man. I would definitely recommend the book for anyone who wants to get a feel for Shinran’s core ideas.

Thank you so much for reading!

**Want to take a deeper dive into Tannisho in Japanese?**

My father recommended a three volume series of transcribed recorded lectures『歎異抄』師訓篇を読む by 梯 實圓 (自照社出版). I’m certain it’ll open up a door to Tannisho in a more fulfilling way.

Words

- Shinran (親鸞)

- Jodo Shin / True Pure Land sect (浄土真宗)

- Akunin shoki (悪人正機)

- Tannisho (歎異抄)

- Amida Nyorai (阿弥陀如来)

- Gutoku (愚禿)

- Enryakuji temple (延暦寺)

- Miotsukushi (澪標) by TONOMURA Shigeru (外村繁)

- Namu Amida Butsu (南無阿弥陀仏)

More about Nakanishi's The Japanese Linguistic Landscape:

Purchase it here:

The Japanese Linguistic Landscape: Reflections on Quintessential Words by NAKANISHI Susumu. Translated by Ryan Shaldjian Morrison.

The Japanese Linguistic Landscape: Reflections on Quintessential Words by NAKANISHI Susumu. Translated by Ryan Shaldjian Morrison.

Published by: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture (JPIC)

ISBN 978-4-86658-068-5

First English edition: August 2019

This book is a translation of Utsukushiki Nihongo no Fukei (美しき日本語の風景) and selections of Part I and II in Kotoba no Kokoro (ことばのこころ)

NAKANISHI Susumu (Author)

Nakanishi was born in Tokyo in 1929. He earned his doctorate in literature in 1959 from the University of Tokyo. In 2013, he was awarded the Order of Culture, Japan’s top prize for cultural contribution. He was awarded the Yomiuri Prize for Literature in 1964, the Japan Academy Prize in 1970, and Watsuji Tetsuro Culture Prize in 1991 for his pioneering work on the Manyoshu (万葉集)ーJapan’s oldest poetry anthology. He has been appointed poetry composer for the annual Utakai Hajime (First Poetry Reading) held at the Tokyo Imperial Palace. In 2004, he was recognized as a Person of Cultural Merit. In 2005, he was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure.

Ryan Shaldjian Morrison (Translator)

Morrison is a literary translator and scholar of Japanese literature. He is currently a tenured lecturer at Nagoya University of Foreign Studies. He received his first M.A. in Japanese literature from Arizona State University in 2004, his second M.A. in Japanese literature from Sophia University (Tokyo) in 2009, and his Ph.D. from the University of Tokyo in 2016 for his dissertation on the modernist writer ISHIKAWA Jun.